Last week, a 12-person working group(the so-called Group of Twelve), set up by the German and French ministers for Europe Anna Lührmann and Laurence Boone, presented a report on the possible reform of the EU’s architecture ahead of a possible enlargement to the Union that would take place in coming years. The report presents various options to change the Treaties that govern how the EU functions, as well as different solutions to make the EU decision-making process fit for the future, even in the case of it consisting of a growing number of countries.

In a nutshell, the main aim of the reform is to overcome the unanimity vote that is required for the most relevant decisions made by the EU, and to increase the instances in which qualified majorities or even simple majorities may instead be sufficient. The EU has previously experienced the implications of “enlarging” before “reforming”, after several new member states from Central and Eastern Europe were admitted in the EU in 2004. Giving the veto power to new entrants, including smaller countries, has implied a significant slowdown in the decision-making process of the EU, which in some cases closely resembles sclerosis and paralysis.

In the not-so-distant future, the EU may need to enlarge further, for example to allow the accession of Ukraine, or of some West Balkans states. The accession of Ukraine would be a life-changing experience for the EU. Almost all development funds would be re-directed from the EU periphery (the South as well as the Centre-Eastern part of the EU) to Ukraine. All agricultural subsidies, which are a large component of the EU budget, would be absorbed by Ukraine. We saw in recent days an example of the conflict that could emerge as a result, when Poland threatened to suspend its supply of weapons to Ukraine because its farmers thought that they were being damaged by the import of grains from Ukraine.

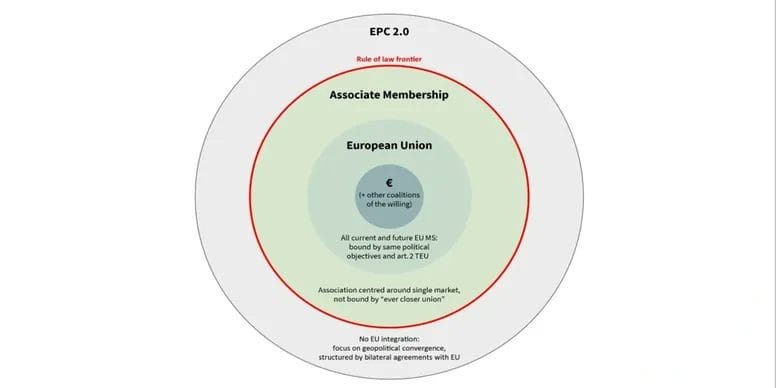

So, the EU needs to reform to be fit for purpose in the future also. One way it would enlarge would be by re-arranging the various forms of association within the European continent into four concentric – or overlapping – circles (see picture above). The inner circle would be represented by the eurozone, plus other “coalitions of the willing” that may want further integration in specific areas, for example through forms of “enhanced cooperation”. The second circle would be the EU.

The third circle, and the first circle to be outside of the EU (called “Associate Membership”), would be represented by nations such as “EEA countries, Switzerland or even the UK,” which have strong ties with the EU but “would not be bound to ‘ever closer union’ and further integration, nor would they participate in deeper political integration in other policy areas such as Justice and Home Affairs or EU citizenship.” Beyond this third circle, there would also be an outer circle of countries belonging to a reformed European Political Community (so-called “EPC 2.0”), which “would not include any form of integration with binding EU law or specific rule of law requirements and would not allow access to the single market,” so beyond what the report calls the “rule of law border” that would stop with the third circle. We have discussed the relevance of this EPC grouping in our column of June 5th, 2023.

These proposals recall very closely what we discussed in our column of May 2ndm 2022, titled “The War In Ukraine Resurrects The Idea Of Organizing Europe In Concentric Circles,” which in turn was based on several publications I wrote several years ago (including here and here). My outer circle “Common European Space” is divided in the Group of Twelve’s report into the two outer circles “Associate Membership” and “EPC 2.0,” but – in substance – the division of concentric circles remains the same.

Most importantly, the re-grouping into concentric circles is fundamentally different from the idea of a “multi-speed” Europe. With multiple speeds, the various countries were to aim at reaching the same end-point (an “ever closer union”) at different times. With concentric circles, not only the speed, but especially the destination of countries would be different. Some countries would never join the EU, let alone the Eurozone, while remaining either closely or loosely associated with the EU; for example the UK and – say – Azerbaijan, respectively. Reforming and enlarging the EU according to the proposal of this report seems essential for the survival of the EU in the long run.